Holland and its People, by Edmondo de Amicis. First published in Italian as `Olanda` (1874). This translation by Caroline Tilton (1890). OCR-Scanned in 1998 by Francisco van Jole from the 1890 edition published by G.P. Putnam`s Sons (The Knickerbocker Press). This text can be used freely but please leave these credits intact.

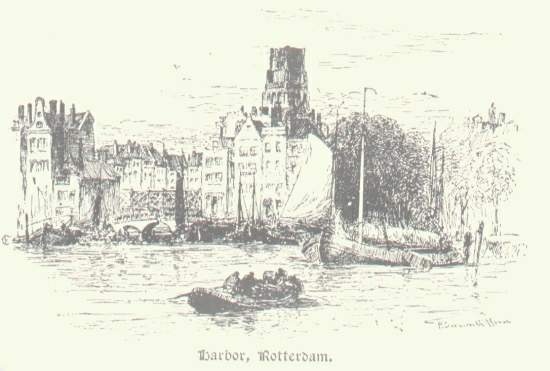

IT is difficult to make much of the city of Rotterdam, entering it at night. The carriage passed almost immediately over a bridge that resounded hollowly beneath it, and whilst I thought myself, and was in fact, within the city, I saw with amazement, on my right and left, two rows of ships vanishing in the gloom.

Leaving the bridge, we passed through a street, lighted, and full of people, and found ourselves upon another bridge, and between two rows of vessels, as before. And so on from bridge to street, from street to bridge, and to increase the confusion, an illumination of lamps at the corners of houses, lanterns on masts of ships, light-houses on the bridges, small lights under the houses, and all these lights reflected in the water. All at once the carriage stopped, people crowded about; I looked out, and saw a bridge in the air. In answer to my question, some one said that a vessel was passing. We went on again, seeing a perspective of canals and bridges, crossing and recrossing each other, until we came to a great square, sparkling with lights, and bristling with masts of ships, and finally we reached our inn in an adjacent street.

My first care on entering my room, was to see whether Dutch cleanliness deserved its fame. It did, indeed, and may be called the religion of cleanliness. The linen was snow-white, the window-panes transparent as the air, the furniture shining like crystal, the floors so clean that a microscope could not discover a black speck. There was a basket for waste paper, a tablet for scratching matches, a dish for cigar ashes, a box for cigar stumps, a spittoon, and a boot-jack; in short, there was no possible pretext for soiling any thing.

My room examined, I spread a map of Rotterdam upon the table, and made some preparatory studies for the morrow.

It is a, singular thing that the great cities of Holland, although built upon a shifting soil, and amid difficulties of every kind, have all great regularity of form. Amsterdam is a semicircle, the Hague square, Rotterdam an equilateral triangle. The base of the triangle is an immense dyke, which defends the city from the Meuse, and is called the Boompjes, signifying, in Dutch, small trees, from a row of little elms, now very tall, that were planted when it was first constructed.

Another great dyke forms a second bulwark against the river, which divides the city into two almost equal parts, from the middle of the left side to the opposite angle. That part of Rotterdam which is comprised between the two dykes is all canals, islands, and bridges, and is the new city that which extends beyond the second dyke is the old city. Two great canals extend along the other two sides of the town to the apex, where they meet, and receive the waters of the river Rotte, which with the affix of dam, or dyke, gives its name to the city.

Having thus fulfilled my conscientious duty as a traveller, and with many precautions not to soil, even by a breath, the purity of that jewel of a chamber, I abandoned myself with humility to my first Dutch bed.

Dutch beds, I speak of those in the hotels, are generally short and wide, and occupied, in a great part, by an immense feather pillow in which a giant's head would be overwhelmed; I may add that the ordinary light is a copper candlestick, of the size of a dinner-plate, which might sustain a torch, but holds, instead, a tiny candle about the size of a Spanish lady's finger.

In the morning I made haste to rise and issue forth into the strange streets, unlike any thing in Europe. The first I saw was the Hoog Straat, a long straight thoroughfare running along the interior dyke.

The unplastered houses, of every shade of brick, from the darkest red to light rose color, chiefly two windows wide and two stories high, have the front wall rising above and concealing the roof, and in the shape of a blunt triangle surmounted by a parapet. Some of these pointed façades rise into two curves, like a long neck without a head; some are cut into steps like the houses that children build with blocks; some present the aspect of a conical pavilion, some of a village church, some of theatrical cabins. The parapets are, in general, bordered by white stripes, coarse arabesques in plaster, and other ornaments in very bad taste; the doors and windows are bordered by broad white stripes; other white lines divide the different stories; the spaces between the doors in front are marked by white wooden panels; so that two colors, white and red, prevail everywhere, and as in the distance the darker red looks black, the prospect is half festive, half funereal, all the houses looking as if they were hung with white linen. At first I had an inclination to laugh, for it seemed impossible that it could have been done seriously, and that quiet, sober people lived in those houses. They looked as if they had been run up for a festival, and would presently disappear, like the paper framework of a grand display of fireworks.

Whilst I stood vaguely looking at the street, I noticed one house that puzzled me somewhat; and thinking that my eyes had been deceived, I looked more carefully at it, and compared it with its neighbors. Turning into the next street, the same thing met my astonished gaze.There is no doubt about it. The whole city of Rotterdam presents the appearance of a town that has been shaken smartly by an earthquake, and is on the point of falling into ruin.

All the houses -- in any street one may count the exceptions on his fingers -- lean more or less, but the greater part of them so much that at the roof they lean forward at least a foot beyond their neighbors, which may be straight or not so visibly inclined; one leans forward as if it would fall into the street, another backward, another to the left, another to the right; at some points six or seven contiguous houses all lean forward together, those in the middle most, those at the ends less, looking like a paling with the crowd pressing against it. At another point two houses lean together as if supporting one another. In certain streets the houses for a long distance lean all one way, like trees beaten by a prevailing wind; and then another long row will lean in the opposite direction, as if the wind had changed. Sometimes there is a certain regularity of inclination that is scarcely noticeable; and again, at crossings and in the smaller streets, there is an indescribable confusion of lines, a real architectural frolic, a dance of houses, a disorder that seems animated. There are houses that nod forward as if asleep, others that start backward as if frightened; some bending toward each other, their roofs almost touching, as if in secret conference; solve falling upon one another as if they were drunk, some leaning backward between others that lean forward like malefactors dragged onward by their guards; rows of houses that curtsey to a steeple, groups of small houses all inclined toward one in the middle, like conspirators in conclave.

Observe them attentively one by one, from top to bottom, and they are as interesting as pictures.

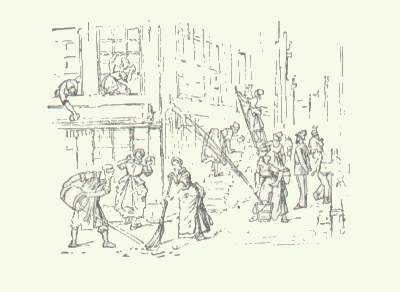

In some, upon the summit of the façade, there projects from the middle of the parapet a beam, with cord and pulley to pull up baskets and buckets. In others, jutting from a round window, is the carved head of a deer, a sheep, or a goat. Under the head, a line of whitewashed stone or wood cuts the whole façade in half. Under this line there are two broad windows with projecting awnings of striped linen; under these again, over the upper panes, a little green curtain; below this green curtain, two white ones, divided in the middle to show a suspended bird-cage or a basket of flowers. And below the basket or the cage, the lower panes are covered by a network of fine wire that prevents the passer-by from seeing into the room. Within, behind the netting there stands a table covered with objects in porcelain, crystal flowers, and toys of various kinds. Outside, on the stone sill, is a row of small flowerpots. From the stone sill, or from one side, projects an iron stem curving upwards, which sustains two small mirrors joined in the form of a book, movable, and surmounted by another, also movable, so that those inside the house can see, without being seen, every thing that passes in the street. On some of the houses there is a lamp projecting between the two windows, and below is the door of the house, or a shop-door. If it is a shop, over the door there is the carved head of a Moor with his mouth wide open, or that of a Turk with a hideous grimace; sometimes there is an elephant, or a goose; sometimes a horse's or a bull's head, a serpent, a half-moon, a windmill, or an arm extended, the hand holding some object of the kind sold in the shop. If it is the house-door-always kept closed --there is a brass plate with the name of the occupant, another with a slit for letters, another with the handle of a bell, the whole, including locks and bolts, shining like gold. Before the door there is a small bridge of wood, because in many of the houses the ground-floor or basement is much lower than the street, and before the bridge two little stone columns surmounted by two balls; two more columns in front of these are united by iron chains, the large links of which are in the form of crosses, stars, and polygons; in the space between the street and the house are pots of flowers and at the windows Of the ground-floor more flowerpots and curtains. In the more retired streets there are bird-cages on both sides of the windows, boxes full of green growing things, clothes hung out to air or dry, a thousand objects and colors, like a universal fair.

But without going out of the older town one need only go away from the centre to see something new at every step.

In some narrow straight streets one may see the end suddenly closed as if by a curtain concealing the view; but it disappears as it came, and is recognized as the sail of a vessel moving in a canal. In other streets a network of cordage seems to stop the way; the rigging of vessels lying in some basin. In one direction there is a drawbridge raised, and looking like a gigantic swing provided for the diversion of the people who live in those preposterous houses; and in another there is a windmill, tall as a steeple and black as an antique tower, moving its arms like a monstrous firework. On every side, finally, among the houses, above the roofs, between the distant trees, are seen masts of vessels, flags, and sails and rigging, reminding us that we are surrounded by water and that the city is a seaport.

Meantime the shops were opened and the streets became full of people. There was great animation, but no hurry, the absence of which distinguishes the streets of Rotterdam from those of London, between which some travellers find great resemblance, especially in the color of the houses and the grave aspect of the inhabitants. White faces, pallid faces, faces the color of Parmesan cheese; light hair, very light hair, reddish, yellowish; broad beardless visages, beards under the chin and around the neck; blue eyes, so light as to seem almost without a pupil; women stumpy, fat, rosy, slow, with white caps and ear-rings in the form of corkscrews; these are the first things one observes in the crowd.

But for the moment it was not the people that most stimulated my curiosity. I crossed the Hoog Straat, and found myself in the new city. Here it is impossible to say if it be port or city, if land or water predominate, if there are more ships than houses, or vice versa.

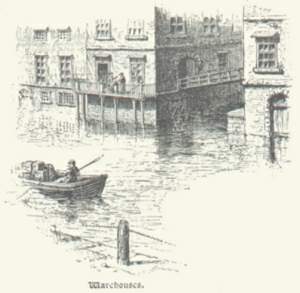

Broad and long canals divide the city into so many islands, united by drawbridges, turning bridges, and bridges of stone. On either side of every canal extends a street, flanked by trees on one side and houses on the other. All these canals are deep enough to float large vessels, and all are full of them from one end to the other, except a space in the middle left for passage in and out. An immense fleet imprisoned in a city.

When I arrived it was the busiest hour, so I planted myself upon the highest bridge over the principal crossing. From thence were visible four canals, four forests of ships, bordered by eight files of trees; the streets were crammed with people and merchandise; droves of cattle were crossing the bridges; bridges were rising in the air, or opening in the middle, to allow vessels to pass through, and were scarcely replaced or closed before they were inundated by a throng of people, carts, and carriages; ships came and went in the canals, shining like models in a museum, and with the wives and children of the sailors on the decks; boats darted from vessel to vessel; the shops drove a busy trade; servant-women washed the walls and windows and all this moving life was rendered more gay and cheerful by the reflections in the water, the green of the trees, the red of the houses, the tall windmills, showing their dark tops and white sails against the azure of the sky, and still more by an air of quiet simplicity not seen in any other northern city.

I took observations of a Dutch vessel. Almost all the ships crowded in the canals of Rotterdam are built for the Rhine and Holland; they have one mast only, and are broad, stout, and variously colored like toy ships. The hull is generally of a bright grass-green, ornamented with a red or a white stripe, or sometimes several stripes, looking like a band of different colored ribbons. The poop is usually gilded. The deck and mast are varnished and shining like the cleanest of house-floors. The outside of the hatches, the buckets, the barrels, the yards, the planks, are all painted red, with white or blue stripes. The cabin where the sailors' families are is colored like a Chinese kiosk, and has its windows of clear glass, its white muslin curtains tied up with knots of rose-colored ribbon. In every moment of spare time, sailors, women, and children are busy washing, sweeping, polishing every part with infinite care and pains; and when their little vessel makes its exit from the port, all fresh and shining like a holiday-coach, they all stand on the poop and accept with dignity the mute compliments which they gather from the glances of the spectators along the canals.

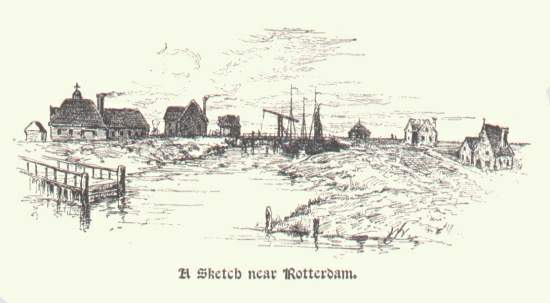

From canal to canal, and from bridge to bridge, I finally reached the dyke of the Boompjes upon the Meuse, where boils and bubbles all the life of the great commercial city. On the left extends a long row of small, many-colored steamboats, which start every hour in the day for Dordrecht, Arnhem, Gouda, Schiedam, Briel, Zealand, and continually send forth clouds of white smoke and the sound of their cheerful bells. To the right lie the large ships which make the voyage to various European ports, mingled with fine three-masted vessels bound for the East Indies with names written in golden letters -- Java, Sumatra, Borneo, Samarang, -- carrying the fancy to those distant and savage countries like the echoes of far-a-way voices. In front of the Meuse, covered with boats and barks, and the distant shore with a forest of beech trees, windmills, and towers; and over all the unquiet sky, full of gleams of light, and gloomy clouds, fleeting and changing in their constant movement, as if repeating the restless labor on the earth below.

Rotterdam, it must be said here, is, in commercial importance, the first city in Holland after Amsterdam. It was already a flourishing town in the thirteenth century. Ludovico Guicciardini, in his work on the Low Countries, already cited, adduces a proof of the wealth of the city in the sixteenth century, saying that in one year nine hundred houses that had been destroyed by fire were rebuilt. Bentivoglio, in his history of the war in Flanders, calls it "the largest and most mercantile of the lands of Holland." But its greatest prosperity did not begin until 1830, or after the separation of Holland and Belgium, when Rotterdam seemed to draw to herself every thing that was lost by her rival, Antwerp. Her situation is extremely advantageous. She communicates with the sea by the Meuse, which brings to her ports in a few hours the largest merchantmen; and by the same river she communicates with the Rhine, which brings to her from the Swiss mountains and Bavaria immense quantities of timber -- entire forests that come to Holland to be transformed into ships, dykes, and villages. More than eighty splendid vessels come and go, in the space of nine months, between Rotterdam and India. Merchandise flows in from all sides in such great abundance that a large part of it has to be distributed through the neighboring towns. Meantime, Rotterdam is growing; vast store-houses are now in process of construction, and the works are commenced for an enormous bridge which will cross the Meuse and the entire city, thus extending the railway which now stops on the left bank of the river, if not to the port of Delft, at least to its junction with the road to the Hague.

Rotterdam, in short, has a future more splendid than that of Amsterdam, and has long been regarded as a rival by her elder sister. She does not possess the wealth of the capital, but is more industrious in increasing what she has; she dares, risks, under-takes, like a young and adventurous city. Amsterdam, like a merchant grown cautious after having made his fortune by hazardous undertakings, begins to doze over her treasures. At Rotterdam, fortunes are made; at Amsterdam, they are consolidated; at The Hague, they are spent.

It may be understood from this that Rotterdam is regarded somewhat in the light of a by parvenu the other two cities; and also for another reason: that she is simply a trader; occupied only in trade, and has but little aristocracy, and that little modest and not rich. Amsterdam, on the contrary, contains the flower of the mercantile patriciate; Amsterdam has picture-galleries, protects art and literature; but not withstanding her superiority each is jealous of the other; what one does the other tries to do; what the government accords to one the other wants also. At this very moment (1874) both are cutting canals to the sea. It is not yet quite certain what use can be made of these two canals; but that does not matter. So children act: Peter has a horse, I want a horse too, and Grandpapa Government must content both big and little.

Having visited the port, I traversed the dykes of the Boompjes, along which extends an uninterrupted line of big, new houses, in the style of Paris and London, houses which, as is usual, the inhabitants admire, and the stranger never looks at, or looks at them with dislike; then returning, I re-entered the city, and came to the corner formed by the Hoog Straat and one of the two long canals that bound the city on the east. It is the poorest quarter of the town; the streets are narrow, and the houses smaller and more crooked than in other parts; in some you can touch the roof with your hand. The windows are about afoot from the ground, and the doors so low that you must stoop to enter them. Nevertheless, there is no appearance of misery. Even here the windows have their small looking-glasses-spies, as they are called in Holland, --their flower-pots, and their white curtains; and the doors, painted green or blue, stand wide open, giving a view of the bedroom, the kitchen, all the internal arrangements; tiny rooms like boxes, but every thing in them ranged in older, and clean and bright as in gentlemen's houses. There is no dirt in the streets, no bad smells, not a rag to be seen, or a hand held out to beg; there is an atmosphere of cleanliness and well-being which makes one blush for the miserable quarters where the poor are crowded in our cities, not excepting Paris, which has its Rue Mouffetard.

On my way back to my hotel I passed through the great market-place in the middle of the city, not less peculiar than all its surroundings.

It is both a public square and a bridge, and connects the Hoog Straat, or principal dyke, with another quarter of the city surrounded by canals. This airy place is bordered on three sides by old buildings and a long, dark, narrow canal, like a street in Venice; the fourth side is open upon a kind of basin formed by the largest canal, which communicates with the river Meuse. In the middle of the market-place, surrounded by heaps of vegetable, fruit, and earthenware pots and pans, stands the statue of Desiderius Erasmus, the first literary light of Holland; That Gerrit Gerritz -- for he assumed the Latin name himself, according to the custom of writers in his day -- that Gerrit Gerritz belonged, by his education, his style, and his ideas, to the family of the humanists and erudite of Italy; a fine writer, profound and indefatigable in letters and science, he filled all Europe with his name between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries; he was loaded with favors by the popes, and sought after and entertained by princes; and his "Praise of Folly," written in Latin like the rest of his innumerable works, and dedicated to Sir Thomas More, is still read. The bronze statue, erected in 1622, represents Erasmus dressed in a furred gown, with a cap of the same, a little bent forward as if walking, and in the act of reading a large book, held open in the hand; the pedestal bears a double inscription, in Dutch and Latin, calling him, "Vir sæculi sui primarius" and "Civis omnium præstantissimus." In spite of this pompous eulogium, however, poor Erasmus, planted there like a municipal guard in the market-place, makes but a pitiful figure. I do not believe that there is in the world another statue of a man of letters that is, like this, neglected by the passer-by, despised by those about it, commiserated by those who look at it. But who knows whether Erasmus, acute philosopher as he was, and must he still, be not contented with his corner, the more that it is not far from his own house, if the tradition is correct? In a small street near the market-place, in the wall of a little house now occupied as a tavern, there is a niche with a bronze statuette representing the great writer, and under it the inscription, "Hæc est parva domus magnus qua natus Erasmus."

In one corner of this square there is a little house known as the "House of Fear," upon the wall of the House which may be seen an ancient painting whose subject I have forgotten. The name of the "House of Fear" was given to it, says the tradition, because when the Spaniards sacked the city the most conspicuous personages took refuge in this house and remained shut up in it three days without food. And this is not the only memorial of the Spaniards at Rotterdam. Many edifices, built during their domination, show the style of architecture which was then in use in Spain; and some still bear Spanish inscriptions. In Holland inscriptions upon houses are very common. They glory in their old age like bottles of wine, and bear the (late of the year of their construction inscribed in large characters on the façade.

In the market-place I had a good opportunity for observing the ear-rings of the women, which are well worthy of remark.

At Rotterdam I saw only the ear-rings in use in South Holland; but even so, their variety is very great. They are all alike, however, in one particular, that instead of being in the ears, they are attached to the two extremities of an ornament in gold, silver, or gilt copper, which encircles the head like a diadem and ends on the temples. The commonest form of ear-ring is a spiral of five or six rows, often very large, and setting out on either side of the face in a very conspicuous fashion. Many of the women wear ordinary ear-rings attached to these spiral ornaments, which dangle over the cheeks and fall down upon the bosom. Some have a second circlet of gold, much chased and ornamented with flowers and buttons in relief, that passes over the forehead. Almost all wear the hair smooth and tight, and covered with a night-cap like heed-dress of lace and muslin, falling in a sort of veil over the neck and shoulders.

This Arab-like veil and their extravagant and preposterous ear-rings give them a mixed regal and barbaric aspect, which, if they were not as fair as they are, might cause them to be mistaken for the women of some savage country who hail preserved the head-dress of their ancient costume. I do not wonder that some travellers, seeing them for the first time, should have believed that their ear-rings were a combination of ornament and implement, and asked their purpose. But we may also suppose that they serve as defensive arms, since any impertinent person, who should put his face too near that of the wearer, would find his approach warded off by these impediments. Worn chiefly by the peasants, these ear-rings and their accessories are generally in gold, and cost a large sum; but I saw still greater riches among the Dutch peasantry.

This Arab-like veil and their extravagant and preposterous ear-rings give them a mixed regal and barbaric aspect, which, if they were not as fair as they are, might cause them to be mistaken for the women of some savage country who hail preserved the head-dress of their ancient costume. I do not wonder that some travellers, seeing them for the first time, should have believed that their ear-rings were a combination of ornament and implement, and asked their purpose. But we may also suppose that they serve as defensive arms, since any impertinent person, who should put his face too near that of the wearer, would find his approach warded off by these impediments. Worn chiefly by the peasants, these ear-rings and their accessories are generally in gold, and cost a large sum; but I saw still greater riches among the Dutch peasantry.

Near the market-place is the cathedral, founded towards the end, of the fifteenth century, at the time of the decline of Gothic architecture, then a Catholic church dedicated to St Lawrence, and now the first Protestant church in the city. Protestantism, that vandal of religion, entered the ancient churches with a pick and a white-wash brush, and with pedantic fanaticism eradicated every thing that was beautiful and splendid, reducing it to a, naked whiteness and coldness, such as in the times of the false and lying gods might have suited a temple sacred to the goddess of Ennui. An immense organ, with about fifty thousand pipes, giving among other sounds the effect of an echo; some tombs of admirals, adorned with long inscriptions in Dutch and Latin; numerous benches; a few boys with their caps on their heads, a group of women, chattering together in loud voices; an old man in a corner, with a cigar in his mouth -- this was all I saw. That was the first Protestant church in which I set my foot, and I confess that it made a disagreeable impression upon me. I was half saddened, half scandalized. I compared its desolate and bare interior with the magnificent cathedrals of Spain and Italy, where, amid the soft mysterious light and through clouds of incense, the eye encounters the loving looks of saints and angels on the walls, pointing us to heaven; where we see so many images of innocence that calm our souls, and of pain that help us to suffer, while they inspire resignation, peace, the sweetness of forgiveness, where the homeless and the hungry, driven from the rich man's door, may pray amid marble and gold, as in a kingdom where he is not disdained, amid a pomp and splendor that does not humiliate him, that even honors and comforts his misery; those cathedrals where we knelt as children at our mother's side, and felt for the first time a sweet security of living again one day with her in those azure depths depicted upon the domes above our heads. Comparing the church with those cathedrals, I discovered that I was a better Catholic than I had thought, and I felt the truth of those words of Emilio Castelar: " Well, yes, I am a rationalist; but if one day I should wish to return in into the bosom of a religion, I would go back to that splendid one of my fathers, and not to this squalid and naked religion that saddens my eyes and my heart!"

From the top of the tower the whole of Rotterdam call be seen at a glance, with all its little sharp red roofs, its broad canals, its ships scattered among houses, and all about the city a vast green plain, intersected by canals bordered by trees, sprinkled with windmills, and villages hidden in masses of verdure, showing only the tops of their steeples. When I was there the sky was clear, and I could see the waters of the Meuse shilling from the neighborhood of Bois-le-Duc, nearly to its mouth; the steeples of Dordrecht, Leyden, Delft, The Hague, and Gouda were visible, but neither far nor near was there a hill, a rising ground, a swell to interrupt the straight and rigid line of the horizon. It was like a green and motionless sea, where the steeples represented masts of ships at anchor. The eye roamed over that immense space with a sense of repose, and I felt, for the first time, that indefinable sentiment inspired by the Dutch landscape, which is neither pleasure, nor sadness, nor ennui, but a mixture of all three, and which holds you for a long: time silent and motionless.

Suddenly I was startled by the sound of strange music, coming from I knew not where. It was a chime of bells ringing a lively air, the silvery notes now falling slowly one by one, and now coming in groups, in strange flourishes, in trills, in sonorous chords, a quaint dancing strain, somewhat primitive, like the many-colored city, over which its notes hovered like a flock of wild birds, or like the city's natural voice, an echo of the antique life of her people, recalling the sea, the solitudes, the huts, and making one smile and sigh at the same moment. All at once the music ceased, and the clock struck the hour. At the same moment other steeples took up the airy strains, playing airs of which only the higher notes reached my ears, and then they also struck the hour. This aërial concert is repeated every hour of the day and night in all the steeples of Holland, the tunes beings national airs, or from German or Italian operas. Thus in Holland the passing hour sings, as if to distract the mind from sad thoughts of flying time, and its song is of country, faith, and love, floating in harmony above the sordid noises of the earth.

The Hollanders eat a great deal. Their greatest pleasures, as Cardinal Bentivoglio says, are those of the table. Their appetites are voracious, and they care more for quantity than quality. In the old time they were laughed at by their neighbors not only for the rudeness of their manners, but for the simplicity of their nutriment, and were called milk and cheese eaters. They eat, in general, five times a day: at breakfast, tea, coffee, milk, bread, cheese, and butter; a little before noon, a good luncheon; before dinner, what might be called a bite -- a biscuit and a glass of wine; then a large dinner; and late in the evening, supper, just so as not to go to bed with an empty stomach. They eat together on every occasion. I do not speak of birth and marriage feasts, which are customary in all countries; but, for example, they have funeral feasts. It is the custom for the friends and acquaintances who have accompanied the funeral procession, to return with the family of the defunct to their house, and there to eat and drink, doing in general great honor to their entertainer. If there were no other witnesses, the Dutch painters all bear testimony to the large part which the table holds in the life of the people. Besides the infinite number of pictures of domestic subjects, in which it might be said that the plate and the bottle are the protagonists, almost all the great pictures that represent historical subjects, burgomasters, civic guards, show them seated at table in the act of biting, cutting, pouring out. Even their great hero, William the Taciturn, the incarnation of new Holland, was an example of this national fondness for eating, and his cook was the first artist of his time; so great a one that the German princes sent beginners to perfect themselves in his school and Philip II, in one of his periods of apparent reconciliation with his mortal enemy, asked for the cook as a present.

But, as has been said, the character of Dutch cookery was rather abundance than refinement. The French, who understand the art, found much to criticise. I remember a writer of certain Mémoires sur la Hollande," who inveighs with lyric force against the Dutch kitchen, saying: "What is this beer soup? this mingling of meats and sweets? this devouring of meat in such quantity without bread? " Other writers have spoken of dining in this country as of a domestic calamity. It is superfluous to say that all this is exaggeration. An ultra-delicate palate can in a short time become accustomed to Dutch cookery. The foundation of the dinner is always a dish of meat with which are served four or five dishes of vegetables or salted meats, of which each one: takes and combines as he likes with the principal dish. The meat is very good, and the vegetables ale exquisite, and cooked in a great variety of ways; the potatoes and cabbages are worthy of special mention, and the art of making an omelet is perfectly understood.

I say nothing of game, fish, milk, and butter, because all these are already known to fame; and I am silent, not to be carried away by enthusiasm, on the subject of that celebrated cheese, wherein when once you have thrust your knife you can never leave off until you have excavated the whole, while desire still hovers over the shell.

A stranger dining for the first time in a Dutch tavern sees a few novelties. First of all he is struck by the great size and thickness of the plates, proportionate to the national appetite; and in many places he will find a napkin of fine white paper, folded in a three-cornered shape, and stamped with a border of flowers, a little landscape in the corner, and the name of the hotel or café, with a Bon appétit in large blue letters. The stranger, to be sure of his facts, will order roast beef, and they will bring him half a dozen slices, as large as cabbage leaves; or a beefsteak, and he is presented with a sort of cushion of bleeding meat, enough to satisfy a family; or fish, and there appears a marine animal as long as the table; and with each of these come a mountain of boiled potatoes and a pot of vigorous mustard. Of bread, a little thin slice about as big as a dollar, most displeasing to us Latins, whose habit it is to devour bread in quantities; so that in a Dutch tavern one must be constantly asking for more, to the great amazement of the waiters. With any one of these three dishes, and a glass of Bavarian or Amsterdam beer, an honest man may be said to have dined. As for wine, whoever has the cramp in his purse will not talk of wine in Holland, since it is extremely dear; but as purses here are pretty generally robust, almost all middle-class Dutchmen and their betters drink it; and there are certainly few countries where so great a variety and abundance of foreign wines are found as in Holland, French and Rhine wines especially.

It is unnecessary to say that Holland is famous for its liquors, and that the most famous of all is that called, from the little town where it is manufactured Schiedam. There are two hundred manufactories of it at Schiedam, which is distant but a few miles from Rotterdam; and to give an idea of the quantity made, I need only mention that thirty thousand swine are fed yearly with the refuse of the distilleries. This famous liquor, when tasted for the first time, is usually accompanied by a triple oath that the taster will never drink another drop of it, if he live a hundred years; but as the French proverb says, "Who drinks, will drink again," and one begins the second time with a morsel of sugar, and then with less, and finally with none at all, until at last, horribile dictu, on pretence of damp and fog, one swallows two small glasses with the ease of a sailor. Next, in order of excellence, comes Curaçoa, a fine, feminine liquor, less powerful than the Schiedam, but very much more so than the sickly sweet stuff that is sold under its name in other countries. After Curaçoa, come many more, of all grades of strength and flavor, with which an expert drinker can give himself, according to his fancy, all the shades of inebriety --the mild, the strong, the talkative, the silent, and thus dispose his brains in such a way that he may see the world according as best suits his humor, as one arranges an optical instrument, changing the colors of the lenses.

The first time one dines in Holland there is a surprise at the moment of paying the bill. I had made a repast that would have been scanty for a Batavian but was quite sufficient for an Italian, and, from what I knew of the dearness of every thing in Holland, I expected one of those shocks to which, according to Theophile Gautier, the only possible answer is a pistol-shot. I was, then, pleasantly surprised when I was told that my account was forty cents, quarante sous; and as in the great cities of Holland every kind of coin is current, I put down two silver francs, and waited for my friend to discover that he had made a mistake. But he looked at the money without any sign of reconsideration, and remarked with gravity: "Forty sous more, if you please.''

The explanation was simple enough. The monetary unit in Holland is the florin, which is worth two Italian lire (francs) and four centimes; consequently the Dutch son and centime are worth just double the Italian soldo and centime; hence my delusion and its cure.

Rotterdam in the evening presents an unusual aspect to the stranger's eye. Whilst in other northern cities at a certain hour of the night all the life is concentrated in the houses, at Rotterdam at that hour it expands into the street. The Hoog Straat is filled until far into the night with a dense throng, the shops are open, because the servants make their purchases in the evening, and the cafes crowded. Dutch cafes are peculiar. In general there is one long room, divided in the middle by a green curtain, which is drawn down at evening and conceals the back part, which is the only part lighted; the front part, closed from the street by large glass doors, is in darkness, so that from without only dark shadowy forms can be seen, and the burning points of cigars, like so many fireflies. Among these dark forms, the vague profile of a woman who prefers darkness to light may be detected here and there.

Next in interest after the cafe come the tobacco shops. There is one at almost every step, and they are without exception the finest in Europe, even surpassing the great tobacco shops of Madrid, where Havana tobacco is sold. In these shops, resplendent with lights like the Parisian cafes, may be found cigars of every form and flavor; and the courteous merchant hands you your purchase neatly done up in fine thin paper, after having cut off the end of one cigar with a little machine.

Dutch shops are illuminated in the most splendid manner; and although in themselves they differ but little from those of other European cities, they still have a peculiar aspect at night because of the contrast between the ground-floor and the rest of the house. Below till is light, color, splendor, and crystal; above, the dark house-front, with its strange angles, steps, and curves. The upper part is old Holland -- simple, dark, and silent; the lower part is the new -- life, fashion, luxury, elegance. Besides this, as all the houses are very narrow, and the shops occupy the entire ground-floor, and are set closely one beside the other, at night, in streets like the Hoog Straat, there is not a bit of wall to be seen, the houses seem to have their ground-floors built of glass, and the street is bordered on either side by two long lines of brilliant illumination, inundating it with light, so that any one can see to pick up a pin.

Walking through Rotterdam in the evening, it is evident that the city is teeming with life and in process of expansion; a youthful city, still growing, and feeling herself every year more and more pressed for room in her streets and houses. In a not far distant future, her hundred and fourteen thousand inhabitants will have increased to two hundred thousand. The smaller streets swarm with children; there is an overflow of life and movement that cheers the eye and heart; a kind of holiday air.

The white and rosy faces of the servant-maids, whose white caps gleam on every side; the serene, visages of shopkeepers slowly imbibing great glassfuls of beer; the peasants with their monstrous ear-rings; the cleanliness; the flowers in the windows; the tranquil and laborious throng; --all give to Rotterdam an aspect of healthful and peaceful content, which brings to the lips the chant of Te Beata, not with the cry of enthusiasm, but with the smile of sympathy.

The white and rosy faces of the servant-maids, whose white caps gleam on every side; the serene, visages of shopkeepers slowly imbibing great glassfuls of beer; the peasants with their monstrous ear-rings; the cleanliness; the flowers in the windows; the tranquil and laborious throng; --all give to Rotterdam an aspect of healthful and peaceful content, which brings to the lips the chant of Te Beata, not with the cry of enthusiasm, but with the smile of sympathy.

When I came back to my hotel, I found a French family occupied in the hall admiring the nails in a door, which looked like so many silver buttons.

The next morning, looking out of my window on the second floor, and observing the roofs of the opposite houses, I recognized, with astonishment, that Bismarck was excusable when he imagined that he saw spectres on the roofs of the Rotterdam houses. From every chimney of all the older buildings rise tubes, curved or straight, crossing and recrossing each other like open arms, like enormous hoots, forked, and in every kind of fantastic attitude, and looking very much as if they had a mutual understanding and might fly about at night with brooms.

Upon descending into the Hoog Straat, I found it was a holiday and very few shops were open; even those few, I was told, would have been closed not many years ago, but now the observance of religious forms, which had once been very rigorous, is beginning to relax. I saw signs of holiday in the dress of the people, especially the men, who -- above all, those of the inferior classes -- have a manifest sympathy for black clothes, and generally wear them on a Sunday: black cravat, black trousers, and a long black surtout reaching to the knee -- a costume which, combined with their slow motions and grave faces, gives them rather the look of a village mayor on his way to assist at an official Te Deum.

But what astonished me was to see, at that early hour, almost every one, rich and poor, men and boys, with a cigar in their mouths. This ill-omened habit of "dreaming with the eyes open," to quote Emile de Girardin in his attack upon smokers, occupies so large a part in the lives of the Dutch people, that I must devote a few words to if.

The Hollanders are, perhaps, of all the northern peoples, those who smoke the most. The humidity of their climate makes it almost a necessity, and the very moderate cost of tobacco renders it accessible to all. To show how deeply rooted is the habit, it is enough to say that the boatmen of the trekschuit, the aquatic diligence of Holland, measure distances by smoke. From here, they say, to such and such a place, it is, not so many miles, but so many pipes.

When you enter a house, after the first salutations, your host offers you a cigar; when you take leave, he hands you another, and often insists upon filling your cigar-case. In the streets you see persons lighting a fresh cigar with the burning stump, of the last one, without pausing in their walk, and with the busy air of people who do not wish to lose a moment of time or a mouthful of smoke. Many go to sleep with pipe in mouth, relight it if they wake in the night, and again in the morning before they step out of bed. "A Dutchman," says Diderot, " is a living alembic." It really does appear that smoking is for him a necessary vital function. Many people think that so much smoke dulls the intelligence. Nevertheless, if there be a people, as Esquiroz justly observes, whose intellect is of the clearest and highest precision, it is the Dutch people. Again, in Holland the cigar is not an excuse for idleness, nor do they smoke in order to dream with their eyes open; every one goes about his business puffing out white clouds of smoke, with the regularity of a factory chimney, and the cigar; instead of being a mere distraction, is a stimulant and an aid to labor. ''Smoke," said a Hollander to me, " is our second breath." Another defined the cigar as the sixth finger of the hand.

Here, apropos of tobacco, I am tempted to record the life and death of a famous Dutch smoker; but I am a little afraid of the shrugs of my Dutch friends, who, relating to me the story, lamented much that when foreigners wrote about Holland they were so apt to neglect things important and honorable to the country, while they occupied themselves with trifles of that nature. It appears to me, however, to be a trifle of so new and original a type, that I cannot restrain my pen.

There was, then, once upon a time, a rich gentleman of Rotterdam, of the name of Van Klaes, who was surnamed Father Great-pipe because he was old, fat, and a great smoker. Tradition relates that he had honestly amassed a fortune as a merchant in India, and that he was a kind-hearted and goodtempered man. On his return from India, he built a beautiful palace near Rotterdam, and in this palace he collected and arranged, as in a museum, all the models of pipes that had ever seen the, sun, in all countries and in every time, from those used by the antique barbarian to smoke his hemp, up to the splendid pipes of meerschaum and amber, carved in relief and bound with gold, such as are seen in the richest Parisian shops. The museum was open to strangers, and to every one who visited it, Van Klaes, after having displayed his vast erudition in the matter of smoking, presented a catalogue of the museum bound in velvet, and filled his pockets with cigars and tobacco.

Mynheer van Klaes smoked a hundred and fifty grammes of tobacco per day, and died at the age of ninety-eight years; so that, if we suppose that he began to smoke at eighteen years of age, in the course of his life he had, smoked four thousand three hundred and eighty-three kilogrammes; with which quantity of tobacco an uninterrupted black line of twenty French leagues in length might be formed. With all this, Mynheer van Klaes showed himself a much greater smoker in death than he had been in life. Tradition has preserved all the particulars of his end. There wanted but a few days to the completion of his ninety-eighth year, when he suddenly felt that his end was approaching. He sent for his notary, who was also a smoker of great merit, and without further preamble, "My good notary," said he, "fill my pipe and your own; I am about to die." The notary obeyed; and when both pipes were lighted, Van Klaes dictated his will, which became celebrated all over Holland.

After having disposed of a large part of his property in favor of relations, friends, and hospitals, he dictated the following article:

" I desire that all the smokers in the country shall be invited to my funeral, by all possible means, newspapers, private letters, circulars, and advertisements. Every smoker who shall accept the invitation shall receive a gift of ten pounds of tobacco and two pipes, upon which shall be engraved my name, my arms, and the date of my death. The poor of the district who shall follow my body to the grave shall receive each man, every year, on the anniversary of my death, a large parcel of tobacco. To all those who shall be present at the funeral ceremonies, I make the condition, if they wish to benefit by my will, that they shall smoke uninterruptedly throughout the duration of the ceremony. My body shall be enclosed in a case lined inside with the wood of my old Havana cigar-boxes. At the bottom of the case shall be deposited a box of French tobacco called caporal, and a parcel of our old Dutch tobacco. At my side shall be laid my favorite pipe and a box of matches, because no one knows what may happen. When the coffin is deposited in the vault, every person present shall pass by and cast upon it the ashes of his pipe.''

The last will and testament of Mynheer van Klaes was rigorously carried out; the funeral was splendid, and veiled in a thick cloud of smoke. The cook of the defunct, who was called Gertrude, to whom her master had left a comfortable income, on condition that she should conquer her aversion to tobacco, accompanied the procession with a paper cigarette in her mouth; the poor blessed the memory of the beneficent deceased, and the whole country rang with his praises, as it still rings with his fame.

Passing along the canal, I saw, with new effects, one of those rapid changes of weather that I have mentioned. All at once the sun vanished, the infinite variety of colors were dimmed, and an autumn wind began to blow. Then to the cheerful, tranquil gayety of a moment before succeeded a kind of timid agitation. The branches of the trees rustled, the flags of the ships streamed out, the boats tied to the piles danced about, the water trembled, the thousand small objects about the houses swung to and fro, the arms of the windmills whirled more rapidly; a wintry chill seemed to run through the whole city, and moved it as if with a mysterious menace. After a moment, the sun burst out again, and with it came color, peace, and cheer. The spectacle made me think that, after all, Holland is not, as many call it, a dreary country; but rather very dreary at times, and at times very gay, according to the weather. It is in every thing the land of contrasts. Under the most capricious of skies dwell the least capricious of peoples; and this solid, resolute, anti orderly race has the most helter-skelter and disorderly architecture that can be seen in the world.

Before entering the Rotterdam Museum, a few observations upon Dutch painting seem opportune, not for '' those who know," be it understood, but for those who have forgotten.

The Dutch school of painting has one quality which renders it particularly attractive to us Italians: it is of all others the most different from our own, the very antithesis, or the opposite pole, of art. The Dutch and Italian schools are the two most original, or, as has been said, the only two to which the title rigorously belongs; the others being only daughters, or younger sisters, more or less resembling them. Thus even in painting Holland offers that which is most sought after in travel and in books of travel: the new.

Dutch painting was born with the liberty and independence of Holland. As long as the northern and southern provinces of the Low Countries remained under the Spanish rule and in the Catholic faith, Dutch painters painted like Belgian painters; they studied in Belgium, Germany, and Italy; Heemskerk imitated Michael Angelo; Bloemaert followed Correggio, and Van Moor copied Titian, not to indicate others; and they were one and all pedantic imitators, who added to the exaggerations of the Italian style a certain German coarseness, the result of which was a bastard style of painting, stilt inferior to the first, childish, stiff in design, crude in color, and completely wanting in chiaroscuro, but not, at least, a servile imitation, and becoming, as it were, a faint prelude of the true Dutch art that was to be.

With the war of independence, liberty, reform, and painting also were renewed. With religions traditions fell artistic traditions; the nude nymphs, Madonnas, saints, allegory, mythology, the ideal -- all the old edifice fell to pieces. Holland, animated by a new life, felt the need of manifesting and expanding it in a new way; the small country, become all at once glorious and formidable, felt the desire for illustration; the faculties, which had been excited and strengthened in the grand undertaking of creating a nation, now that the work was completed, overflowed and ran into new channels; the conditions of the country were favorable to the revival of art; the supreme dangers were conjured away; there was security, prosperity, a splendid future; the heroes had done their duty, and the artists were permitted to come to the front; Holland, after many sacrifices and much suffering, issued victoriously from the struggle, lifted her face among her people and smiled. And that smile is Art.

What that art would necessarily be, might have been guessed, even had no monument of it remained. A pacific, laborious, practical people, continually beaten down, to quote a great German poet, to prosaic realities by the occupations of a vulgar, burgher life; cultivating its reason at the expense of its imagination; living, consequently, more in clear ideas than in beautiful images; taking refuge from abstractions; never darting its thoughts beyond that nature with which it is in perpetual battle; seeing only that which is, enjoying only that which it can possess, making its happiness consist in the tranquil ease and hottest sensuality of a life without violent passions or exorbitant desires;--such a people must have tranquillity also in their art, they must love an art that pleases without startling the mind, which addresses the senses rather than the spirit,--an art full of repose, precision, and delicacy, though material like their lives; in one word, a realistic art in which they can see themselves as they are, and as they are content to be.

The artists began by tracing that which they saw before their eyes--the house. The long winters, the persistent rains, the dampness, the variableness of the climate, obliged the Hollander to stay within doors the greater part of the year. He loved his little house, his shell, much better than we love our abodes, for the reason that he had more need of it, and stayed more within it; he provided it with all sorts of conveniences, caressed it, made much of it; he liked to look out from his well-stopped windows at the falling snow, and the drenching rain, and to hug himself with the thought: " Rage, tempest, I am warm and safe! " Snug in his shell, his faithful housewife beside him, his children about him, he passed the long autumn and winter evenings in eating much, drinking much, smoking much, and taking his well-earned ease after the cares of the day were over. The Dutch painters represented these houses and this life in little pictures, proportionate to the size of the walls on which they were to hang; the bed-chambers that make one feel a desire to sleep, the kitchens, the tables set out, the fresh and smiling faces of the house-mothers, the men at their ease around the fire; and with that conscientious realism which never forsakes them, they depict the dozing cat, the yawning dog, the clucking hen, the broom, the vegetables, the scattered pots and pans, the chicken ready for the spit. Thus they represent life in all its scenes, and in every grade of the social scale--the dance, the conversazione, the orgy, the feast, the game; and thus did Terburg, Metzu, Netscher, Douw, Mieris, Steen, Brauwer, and Van Ostade become famous.

After depicting the house, they turned their attention to the country. The stern climate allowed but a brief time for the admiration of nature, but for this very reason Dutch artists admired her all the more; they saluted the spring with a livelier joy, and permitted that fugitive smile of heaven to stamp itself more deeply on their fancy. The country was not beautiful, but it was twice dear because it had been torn from the sea and from the foreign oppressor. The Dutch artist painted it lovingly; he represented it simply, ingenuously, with a sense of intimacy which at that time was not to be found in Italian or Belgian landscape. The flat, monotonous country had, to the Dutch painter's eyes, a marvellous variety. He caught all the mutations of the sky, and knew the value of the water, with its reflections, its grace and freshness, and its power of illuminating every thing. Having no mountains, he took the dykes for background; and with no forests, he imparted to a simple group of trees all the mystery of a forest; and he animated the whole with beautiful animals and white sails.

The subjects of their pictures are poor enough---; windmill, a canal, a gray sky; -but how they make one think! A few Dutch painters, not content with nature in their own country, came to Italy in search of hills, luminous skies, aid famous ruins; and another band of select artists is the result, Both, Swanevelt, Pynacker, Breenberg, Van Laer, Asselyn. But the palm remains with the landscapists of Holland, with Wynants the painter of morning, with Van der Neer the painter of night, with Ruysdaël the painter of melancholy, with Hobbema the illustrator of windmills, cabins, and kitchen-gardens, and with others who have restricted themselves to the expression of the enchantment of nature as she is in Holland.

Simultaneously with landscape art was born another kind of painting, especially peculiar to Holland --animal painting. Animals are the riches of the country; and that magnificent race of cattle which has no rival in Europe for fecundity and beauty. The Hollanders, who owe so much to them, treat them, one may say, as part of the population; they wash them, comb, them, dress them, and love them dearly. They are to be seen everywhere; they are reflected in all the canals, and dot with points of black and white the immense fields that stretch on every side, giving an air of peace and comfort to every place, and exciting in the spectator's heart a sentiment of arcadian gentleness and patriarchal serenity. The Dutch artists studied these animals in all their varieties, in all their habits, and divined, as one may say, their inner life and sentiments, animating the tranquil beauty of the landscape with their forms. Rubens, Snyders, Paul de Vos, and other Belgian painters, had drawn animals with admirable mastery, but all these are surpassed by the Dutch artists Van der Velde, Berghem, Karel de Jardyn, and by the prince of animal painters, Paul Potter, whose famous "Bull," in the gallery of The Hague, deserves to be placed in the Vatican beside the "Transfiguration" by Raphael. In yet another field are the Dutch painters great --the sea. The sea, their enemy, their power, and their glory, forever threatening their country, and entering in a hundred ways into their lives and fortunes; that turbulent North Sea, full of sinister colors, with a light of infinite melancholy upon it, beating forever upon a desolate coast, must subjugate the imagination of the artist. He, indeed, passes long hours on the shore, contemplating its tremendous beauty, ventures upon its waves to study the effects of tempests, buys a vessel and sails with his wife and family, observing and making notes, follows the fleet into battle, and takes part in the fight; and in this way are made marine painters like Willem van der Velde the elder, and Willem the younger, like Backhuysen, Dubbels, and Stork.

Another kind of painting was to arise in Holland, as the expression of the character of the people and of republican manners. A people which without greatness had done so many great things, as Michelet says, must have its heroic painters, if we may call them so, destined to illustrate men and events. But this school of painting--precisely because the people were without greatness, or, to express it better, without the form of greatness, modest, inclined to consider all equal before the country, because all had done their duty, abhorring adulation, and the glorification in one alone of the virtues and the triumphs of many, --this school has to illustrate not a few men who have excelled, and, a few extraordinary facts, but all classes of citizenship gathered among the most ordinary and pacific of burgher life. From this come the great pictures which represent five, ten, thirty persons together, arquebusiers, mayors, officers, professors, magistrates, administrators, seated or standing around a table, feasting and conversing, of life size, most faithful likenesses, grave, open faces, expressing that secure serenity of conscience by which may be divined rather than seen the nobleness of a life consecrated to one's country, the character of that strong, laborious epoch, the masculine virtues of that excellent generation; all this set off by the fine costume of the time, so admirably combining grace and dignity: those gorgets, those doublets, those black mantles, those silken scarfs and ribbons, those arms and banners. In this field stand pre-eminent Van der Heist, Hals, Govaert Flink, and Bol.

Descending from the consideration of the various kinds of painting, to the special manner by means of which the artist excelled in treatment, one leads all the rest as the distinctive feature of Dutch painting -the light.

The light in Holland, by reason of the particular conditions of its manifestations, could not fail to give rise to a special manner of painting. A pale light, waving with marvellous mobility through an atmosphere impregnated with vapor; a nebulous veil continually and abruptly torn, a perpetual struggle between light and shadow, such was the spectacle which attracted the eye of the artist. He began to observe and to reproduce all this agitation of the heavens, this struggle which animates with varied and fantastic life the solitude of nature in Holland; and in representing it the struggle passed into his soul, and instead of representing, he created. Then he caused the two elements to contend under his hand; he accumulated darkness that he might split and seam it with all manner of luminous effects and sudden gleams of light; sunbeams darted through the rifts, sunset reflections and the yellow rays of lamp-light were blended with delicate manipulation into mysterious shadows, and their dim depths were peopled with half-seen forms; and thus he created all sorts of contrasts, enigmas, play and effect of strange and unexpected chiaroscuro. In this field, among many, stand conspicuous Gerard Douw, the author of the famous four-candle picture, and the great magician and sovereign illuminator, Rembrandt.

Another marked feature of Dutch painting was to be color. Besides the generally accepted reasons that in a country where there are no mountainous horizons, no varied prospects, no great coup d'œil, no forms, in short, that lend themselves to design, the artist's eye must inevitably be attracted by color, and that this must be peculiarly the case in Holland, where the uncertain light, the fog-veiled atmosphere, confuse and blend the outlines of all objects, so that the eye, unable to fix itself upon the form, flies to color as the principal attribute that nature presents to it;--besides these reasons, there is the fact that in a country so flat, so uniform, and so gray as Holland, there is the same need of color as in southern lands there is need of shade. The Dutch artists did but follow the imperious taste of their countrymen, who painted their houses in vivid colors, as well as their ships, and in some places the trunks of their trees and the palings and fences of their fields and gardens; whose dress was of the gayest, richest hues; who loved tulips and hyacinths even to madness. And thus the Dutch painters were potent colorists, and Rembrandt was their chief.

Realism, natural to the calmness and slowness of the Dutch character, was to give to their art yet another distinctive feature, finish, which was carried to the very extreme of possibility. It is truly said that the leading quality of the people may be found in their pictures, viz., patience. Every thing is represented with the minuteness of a daguerreotype; every vein in the wood of a piece of furniture, every fibre in a leaf, the threads of cloth, the stitches in a patch, every hair upon an animal's coat, every wrinkle in a man's face; every thing finished with microscopic precision, as if done with a fairy pencil, or at the expense of the painter's eyes and reason. In reality a defect rather than an excellence, since the office of painting is to represent not what is, but what the eye sees, and the eye does not see every thing; but a defect carried to such a pitch of perfection that one admires, and does not find fault. In this respect the most famous prodigies of patience were Douw, Mieris, Potter, Van der Heist, and, more or less, all the Dutch painters.

But realism, which gives to Dutch art so original a stamp, and such admirable qualities, is yet the root of its most serious defects. The artists, desirous only of representing material truths, gave to their figures no expression save that of their physical sentiments. Grief, love, enthusiasm, and the thousand delicate shades of feeling that have no name, or take a different one with the different causes that give rise to them, they express rarely, or not at all. For them the heart does not beat, the eye does not weep, the lips do not quiver. One whole side of the human soul, the noblest and highest, is wanting in their pictures. More, in their faithful reproduction of every thing, even the ugly, and especially the ugly, they end by exaggerating even that, making defects into deformities, and portraits into caricatures; they calumniate the national type; they give a burlesque and graceless aspect to the human countenance. In order to have the proper background for such figures, they are constrained to choose trivial subjects; hence the great number of pictures representing: beer-shops, and drinkers with grotesque, stupid faces, in absurd attitudes, ugly women, and ridiculous old men; scenes in which one can almost hear the brutal laughter and the obscene words. Looking at these pictures, one would naturally conclude that Holland was inhabited by the ugliest and most ill-mannered people on the earth. We will not speak of greater and worse license. Steen, Potter, and Brauwer, the great Rembrandt himself, have all painted incidents that are scarcely to be mentioned to civilized ears, and certainly should not be looked at. But even setting aside these excesses, in the picture-galleries of Holland there is to be found nothing that elevates the mind, or moves it to high and gentle thoughts. You admire, you enjoy, you laugh, you stand pensive for a moment before some canvas; but, coming out, you feel that something is lacking to your pleasure, you experience a desire to look upon a handsome countenance, to read inspired verses, and sometimes you catch yourself murmuring, half unconsciously: " Oh, Raphael!"

Finally, there are still two important excellences to be recorded of this school of painting-its variety, and its importance as the expression, the mirror, so to speak, of the country. If we except Rembrandt, with his group of followers and imitators almost all the other artists differ very much from one another; no other school presents so great a number of original masters. The realism of the Dutch painters is born of their common lore of nature; but each one has shown in his work a kind of love peculiarly his own; each one has rendered a different, impression which he has received from nature; and all, starting from the same point, which was the worship of material truth, have arrived at separate and distinct goals. Their realism, then, inciting them to disdain nothing as food for the pencil, has so acted that Dutch art succeeds in representing Holland more completely than has ever been accomplished by any other school in any other country. It has been truly said that should every other visible witness of the existence of Holland in the seventeenth century-- her period of greatness--vanish from the earth, and the pictures remain, in them would be found preserved entire the city, the country, the ports, the ships, the markets, the shops, the costumes, the arms, the linen, the stuffs, the merchandise, the kitchen utensils, the food, the pleasures, the habits, the religious belief and superstitions, the qualities and defects of the people; and all this, which is great praise for literature, is no less praise for her sister art.

But there is one great hiatus in Dutch art, the reason for which can scarcely be found in the pacific and modest disposition of the people. This art, so profoundly national in all other respects, has, with the exception of a few naval battles, completely neglected all the great events of the War of Independence among which the sieges of Leyden and of Haarlem alone would have been enough to have inspired a whole legion of painters. A war of almost a century in duration, full of strange and terrible vicissitudes, has not been recorded in one single memorable painting. Art, so varied and so conscientious in its records of the country and its people, has represented no scene of that great tragedy, as William the Silent prophetically named it, which cost the Dutch people, for so long a time, so many different emotions of terror, of pain, of rage, of joy, and of pride!

The splendor of art in Holland is dimmed by that of political greatness. Almost all the great painters were born in the first thirty years of the seventeenth century, or in the last part of the sixteenth; all were dead after the first ten years of the eighteenth, and after them there were no more; Holland had exhausted her fecundity. Already towards the end of the seventeenth century the national sentiment had grown weaker, taste had become corrupted, the inspiration of the painters had declined with the moral energies of the nation. In the eighteenth century, the artists, as if they were tired of nature, went back to mythology, to classicism, to conventionalities; the imagination grew cold, style was impoverished, every spark of the antique genius was extinct. Dutch art still showed to the world the wonderful flowers of Van Huysum, the last great lover of nature, and then folded her tired hands, and let the flowers fall upon his tomb.

The actual gallery of pictures of Rotterdam contains but a small number, among which there are very few by the first artists, and none of the great chefs-d'œuvre of Dutch painting. Three hundred pictures and thirteen hundred drawings were destroyed in a fire in 1864; and of what remained the greater part come from one Jacob Otto Boymans, who left them in his will to the city. In this gallery, therefore, one may enter to make acquaintance with some particular artist, rather than to admire the Dutch school.

In one of the first rooms may be seen a few sketches of naval battles, signed with the name of Willem van der Velde, considered as the greatest marine painter of his time, son of Willem, called the elder, also a marine painter. Father and son had the good-fortune to live in the time of the great maritime wars between Holland, England, and France, and saw the battles with their own eyes. The States of Holland placed a small frigate at the disposition of the elder Van der Velde; the son accompanied his father, and both made their sketches in the midst of the cannon-smoke, sometimes pushing their vessel so near as to cause the admiral to order their withdrawal. Van der Velde the younger greatly surpassed his father, and painted, in general, small pictures-a gray sky, a calm sea, and a sail; but so done that, when fixing your eyes upon them, you seem to smell the briny breezes of the ocean, and the frame appears changed into an open window. This Van der Velde belonged to that group of Dutch painters who loved the water with a kind of fury, and painted, it may be said, upon it. Of these also was Backhuysen, a marine painter of great repute in his own time, and whom Peter the Great, when in Amsterdam, chose for his master. Backhuysen relates of himself, that he went out in a small boat in the midst of a tempest to observe the movement of the waves, and he and his boatmen ran such fearful risks that the latter, more solicitous for their own lives than for his picture, took him back to land, in spite of his orders to the contrary. John Griffier did more. He bought a small vessel at London, which he furnished like a house, and installing his wife and family on board, sailed about in search of views. A tempest having wrecked his vessel on a sand-bank and destroyed every thing he possessed, he, saved by a miracle with his family, went to live at Rotterdam; but soon tiring of life on land, Griffier bought another wretched old boat, recommenced his voyages, and a second time risked his life near Dordrecht; but he still persisted in sailing about as before.

In marine painting, the gallery of Rotterdam has little to show; but landscape is worthily represented by two pictures by Ruysdaël, the greatest of the Dutch painters of rural scenes. These two pictures represent his favorite subjects--namely, woody and solitary places, which inspire, like all his pictures, a vague sentiment of melancholy. The great power of this artist, who stands alone among his brother painters for delicacy of mind and a singular superiority of education, lies in his sentiment. It has been justly said that he makes use of landscape to express his own bitterness and weariness, his own dreams, and that he contemplates his country with a sort of sadness, and creates groves of trees in which to hide it. The veiled light of Holland is the image of his soul; no one feels more exquisitely its melancholy sweetness; no one represents like him, with a ray of languid light, the sad smile of some afflicted creature. It follows as a matter of course that so exceptional a nature was not appreciated by his countrymen till long after his death.

Near one of Ruysdaël's pictures is a group of flowers by a woman painter, Rachel Ruysch, the wife of a portrait-painter of note, born in the second half of the sixteenth century, and dying, pencil in hand, at eighty years of age, after having proved to her husband and the world that a woman may passionately cultivate the fine arts and still find time to bear and bring up tell children.

And since I have mentioned the wife of one artist, it may be here noted, en passant, that a pleasant book might be written upon the wives of the Dutch painters, as well for the variety of their adventures as for the important part which they take in the history of art. Many of them we know by sight from their portraits, made in company with their husbands, their children, their cats, and their hens; and biographers speak of them, denying or confirming reports concerning their conduct. Some even venture to hint that the greater part of these ladies did great wrongs to painting. To me it appears that there were faults on both sides. As for Rembrandt, we know that the happiest period of his life was that between his first marriage and the death of his wife, the daughter of a burgomaster of Leeuwarden; posterity, therefore, owes this lady a debt of gratitude. We know, also, that Van der Helst married, when already advanced in life, a lovely young girl against whom there is nothing to be said; and posterity has to thank her as well, for having cheered the declining years of that great artist. It is true that all the wives of the Dutch painters cannot be spoken of in the same terms. The first of the two wives of Steen, for example, was a frivolous woman who left the beer-shop which she had inherited from her father to fall into ruin; and the second, if all is true that is said of her, was unfaithful to him. The second wife of Heemskerk was a swindler, and her husband was obliged to go about milking excuses for her misdeeds. The wife of Hondekoeter was an odd, illtempered woman, who obliged him to pass his evenings at a tavern in order to be rid of her. The wife of Berghem was an insatiable miser; who would wake him abruptly when he fell asleep over his brushes, and make him work to gain money, while the poor man was constrained to resort to subterfuge in order to retain a little of his own earnings, to buy himself an engraving or two. On the other hand, we should never have done were we to attempt to exhaust the misdeeds of the gentlemen. The painter Griffier forced his wife to go about the world in a boat; the painter Veenir got leave of his spouse to go and spend four months in Rome, and stayed four years; Karel de Jardyn married a rich old woman to pay his debts, and, when they were all paid, left her; Molyn had his wife murdered that he might marry a Genoese. We leave in doubt whether poor Paul Potter was betrayed or no by the wife he loved so madly; and whether the great flower-painter, Huysum, who was devoured by jealousy in the midst of riches and honors, for a wife no longer young or handsome, had any real cause for jealousy, or was merely driven wild with suspicion by the manœuvres of his envious rivals. As an appropriate finish, let us honorably record the three wives of Eglon van der Neer, who crowned him with twenty-five children, which did not, however, prevent him from painting a great number of pictures of every kind, from making numerous journeys, and from cultivating many tulips.

There are in the gallery of Rotterdam a few small pictures by Albert Cuyp, who "gave a part of himself" to Dutch art, and who, in the course of a very long life, painted portraits, landscapes, animals, flowers, winter scenes, moonlight, marine subjects, figures, and left on them all the stamp of original genius; nevertheless, like all the Dutch painters of his day, he was so unfortunate that, up to 1750, or more than fifty years after his death, his best pictures sold for one hundred francs, pictures which are now valued, in England, not in Holland, at one hundred thousand. Almost all his works are now in England.